SIMPLE EXPRESS & SLACK APP TUTORIAL

Express is a ‘minimalist’ framework for node.js applications. It will offer us a fast, relatively simple way to get started building a web application, which in this case will also involve hooks into our Slack team.

This tutorial is really going to build from the ground up, presuming no knowledge of anything. In some cases we'll link out to more detailed and comprehensive intros to what's covered here--but this page is going to teach you the bare minimum required to get this app up and running as efficiently as possible. Key tools covered include:

- javascript

- node.js

- express.js

- html

- css

- js scripting on client side

- mongodb

- slack api

CREATING AN BLANK EXPRESS APP

Here are the steps for creating the blank express app template (and connecting it to github.com).

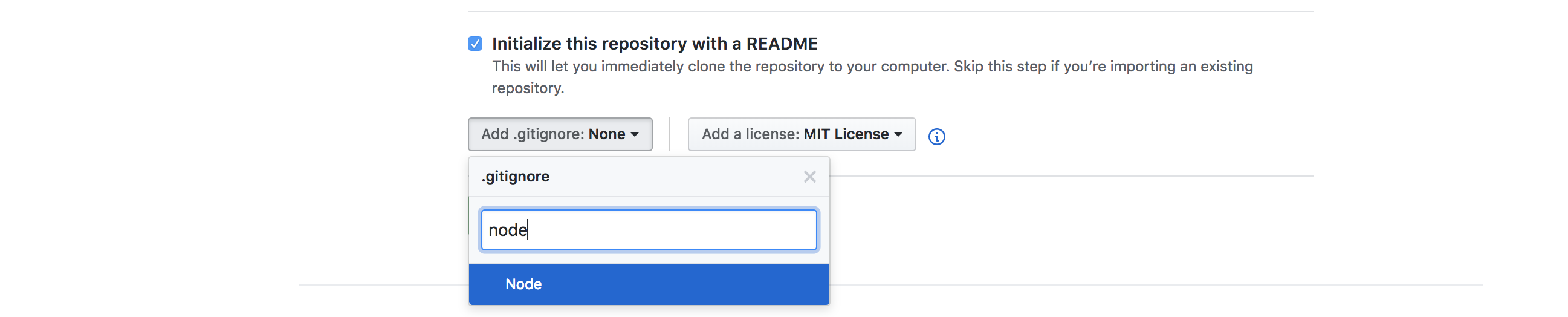

- create an empty repository on github.com. You'll need a github account for this. As you create the repository, you'll be prompted with some settings options: you want to select "node.js" for the

.gitignorefile type, "MIT" for the license type, and you'll want to check the box for “initialize with a README.”

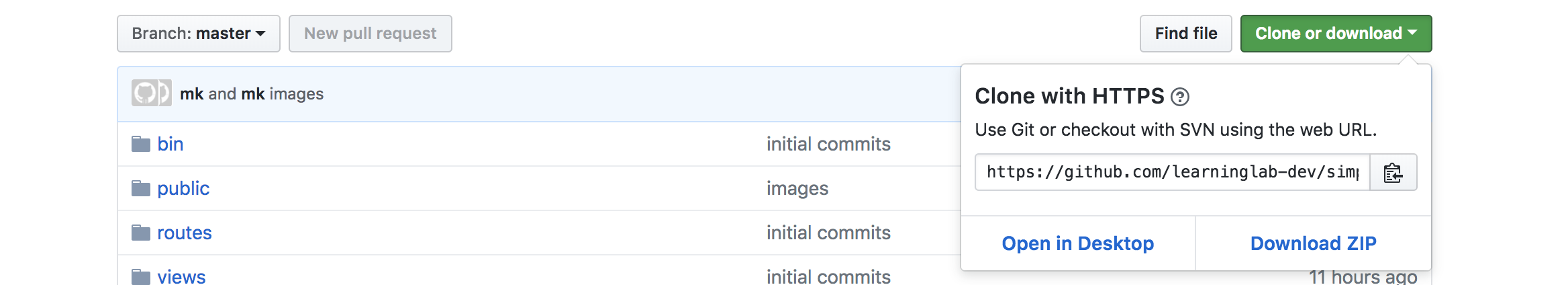

- clone to this repository to your computer by opening up Terminal, navigating to your Development folder (

cd ~/Developmenton our machines) and pasting in thegit clone [REPO_NAME]text that you copy from the repository page. Hit enter and should be all set.

- if you now type

ls(for "list"), you should see a folder with the same name as your repository—this is where you are going to put your app - change directories into your app's root folder by typing

cd [MY_APP] - use express-generator to create an empty express app template by typing

express --view=ejs(go ahead and enterlsto take a look at what has shown up after this command) - install node modules with

npm install - at this point you should be able to type

npm startand then open the app up in your web browser at localhost:3000. - now that we have an blank template, we will want to begin adding some code, so go back to Terminal (and still inside your app's root folder), type

atom .to open up the contents of the current directory in Atom (your text editor). - you’ll see a bunch of folders and files:

binis a folder with an important file that actually starts up your app, but we won’t be touching itpublicis the folder that holds all the files your server will serve up for visitors to your site. All of your ’static’ html pages can go here. More on how to do this in a bit.routesis where we’ll put files that tell your app what to do with users’ requests, like if they type inwww.yourapp.com/theirname/resourcesand you want to read their name and send them back the gifs they’ve saved on your service, say. We won’t actually build a special page for each use that we save inpublic––this would take forever––instead we’ll grab their name, and check for relevant files on the server side, and then plop these into an html template, which brings us to . . .views, which holds our view-templates. In this case we are using ejs (we asked for this when we ran express-generator above), so you’ll see a couple of files with the .ejs extension. We’ll be doing something to one of them soon..gitignoreis the file that tells git what to include and what to exclude when uploading files to github. As long as you selected ‘node’ from the dropdown menu when creating your repository in github, you shouldn’t need to touch this file while doing this tutorial.app.jsis a really key file—the heart of your app (I know we said the that file inbinis where the app starts, but if you check that file out you’ll see that the very first thing it does is bring inapp.jswith arequirestatement, and then it runshttp.createserverfor the app--don't worry if you're new to js and this all looks confusing right now). We are going to add some things toapp.js, but we won’t be deleting or changing anything that’s there right now (in this tutorial anyway).LICENSEis just a text file with the MIT license.package.jsonis important––you can think of it as holding some of the “settings” of the app. It has a list of dependencies, which are the node_modules we’ll need for the project.express-generatorput some there already, and when we typednpm install, npm looked in this file for the dependencies to install and then downloaded them from the cloud.- README.md is where you’ll put notes on your work that you’d like collaborators or other users of your code to see. Whatever you put here will show up on the github page for your repository.

ADDING HTML/CSS

To start out, let’s add a basic html page to our public folder and get it connected to some CSS styles (and in the next step, to a JS script). If you are just using express to start a development server while you explore a client-side js library like d3, for instance, this may be as far as you need to go in this tutorial. If you already know all about HTML and CSS you can skip this one.

In Atom, right-click on the

publicand add a folder for your static page project, in this repo we’ll call oursfirst-project. Inside this folder we’re going to create a file and save it asindex.html.If you already know a bunch about HTML, you can get as elaborate as you’d like at this stage, but you are starting out, copy and paste in the following code:

<body> <h2>steps</h2> <ol> <li>create an index.html page</li> <li>link it to a style.css page</li> <li>link it to a script.js page</li> </ol> </body>The

<and>characters define HTML tags, in this case tags for thebody(which contains the HTML that browser will display),h2for the heading,olfor ordered list, andlifor list elements. Note the way the opening and closing tags for the ordered list (<ol>and</ol>) bracket the list elements, and the way the body tags bracket everything. This nesting structure is a big part of what you'll encounter (and become comfortable with) as you learn HTML.if you now go to localhost:3000/first-project in your web browser you should see the page. For fun, change the

<ol>and</ol>tags (the opening and closing ordered list tags) to<ul>and</ul>(to change it to an unordered list). Play around adding other stuff and other tags, including h1, h2, h3, etc for different headings, p for paragraphs, etc. Don’t forget both opening and closing tags. For a detailed intro go here, for a complete reference go here.you can add as many pages to this folder as you want, but, unlike

index.htmlwhich has a special status, you’d need to type in the complete path to the document if you want your browser to see it. For instance, if I put a file calledmy-gifs.htmlin thefirst-projectfolder, I would access it atlocalhost:3000/first-project/my-gifs.html. Forindex.htmlfiles, you only need to type in the path to the containing folder (localhost:3000/first-project).In order to style the page, we are going to create a

style.cssfile (right in the currentfirst-projectfolder). So right click on yourfirst-projectfolder and create a new file that you save asstyle.css.to connect this file to your html page, you'll need to reopen the

index.htmlfile. And when working with both a css file and an html file in Atom, it's nice to be able to see both at once. So find your html file in the project hierarchy on the left, right-click on it, and select "split right." You should now see your two files side by side.In the

index.htmlfile, add the following lines of code at the top:<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en-US"> <head> <meta charset="UTF-8"> <title>First Project</title> <link rel="stylesheet" href="style.css" type="text/css"> </head>Unlike the

body, theheadof the document doesn't get displayed in the browser, but it still does some useful stuff for us: for instance, it will see to it that the words "First Project" are there in the Chrome or Firefox tab when you open the page in your browser (that's what<title>does); and, most importantly for us right now, it will tell your browser to look in thestyle.cssstylesheet for info on the styles to apply to your various HTML elements.In your

style.cssfile, paste in the following chunk of code:body { background-color: rgba(20,20,20,0.7); color: white; } h2 { font-family: Futura; font-size: 50px; text-transform: uppercase; }Once you save it, you should be able to head back to your browser, hit command+R to reload, and see a dramatic difference. Take a look here to see some of the properties you can change, and start modifying additional attributes of your HTML elements.

The

bodyandh2you see in the css file are called "selectors", and in many cases using the basic HTML elements as your selectors is great (if you want h1's to be huge and h2's to be medium and h3's to be small and blue, say). But sometimes you'll want to target a very specific item on your page, or a specific group of elements, and for this we need to start assigning some of your html elements "classes" and "ids". To get started, grab this chunk of html and paste it in just before your opening<ol>tag to add some "divs"--empty divisions of the site that we'll turn into colored boxes:<div id="big-box"> </div> <div class="small-box"> </div> <div class="small-box"> </div> <div class="small-box"> </div>Reload the browser and you should see . . . nothing new. That's because these divs don't have anything in them, so they are zero pixels high right now. To change this, paste the following into your

style.cssfile..small-box { width: 50px; height: 50px; background-color: rgba(255,0,40,0.7) } #big-box { width: 250px; height: 250px; background-color: rgba(25,80,200,0.7) }The first selector,

.small-boxselects all of the elements with thesmall-boxclass, while the second selects the one element with the idbig-box(ids are exclusive--you can only assign them to one element on a page). And they each define the width, height, and background-color for the divs. If you go back the browser now, you should see your boxes. Change some colors and add some more boxes to get a sense of how all this works. Add some text to a box and see if you can style it.While most of the interactivity we build will happen with javascript, there are some things you can do with just css. For instance, if you paste the following chunk of css at the bottom of your

style.cssfile and then resize your web browser, you should see the#big-boxdiv change size once the browser crosses the 600px-wide threshold:@media screen and (max-width: 600px) { #big-box { width: 100px; } }Try adding a few more lines--you can change anything you'd like, but usually this sort of "media query" is used to give the page a new layout when it's viewed on a small screen (like a phone). Next, add the following little chunk to add some behavior to your

.small-boxdivs whenever a user hovers over them with the mouse:.small-box:hover { background-color: rgba(255,240,40,0.9); width: 250px; }Reload the page and you should see your small red squares turn into wide yellow rectangles when you hover over them. Try adding a

:hoverselector for one of your other elements, and experiment with changing different properties.To add an extra little bit of polish, add this one line to your

.small-boxcss:transition: 1s;. . . reload the page and see how much more elegant the:hovereffects are. If you are lost at this point, you can find the complete css for this practice project in the github repository.

JS on the client side

As we build this web app, we are actually splitting our computers in two, with one half functioning as a server that "serves" up data to send it over to the other half of our machine, which is functioning as the client. As we move through this tutorial you'll get a sense of what sorts of things happen on the "server side" and what sorts of things happen on the "client side".

We're going to be running lots of js code on the server side, but we will also be writing scripts that will run on the client side too, in our users' web browsers. This section gives you a quick taste of how and why you'd do that.

At the bottom of your

index.htmldoc, just before the closing</body>tag, type the following:<script> alert('there is some js running here'); </script>You should now see an alert when you reload the page.

And we could use these alerts to give us info on what our code is doing, but this would get annoying if we had to add a bunch of them. So, instead, we are going to "log" info out to the "console." When we use the

console.logfunction in our server-side code, we'll see the output in our mac's Terminal application, right where we typenpm run devstart. Things are slightly different for our client-side code. For that, we'll need to open up the Developer view in our browser by hitting command + option + "i" . . . and then making sure we've selected "console" from the menu rather than "elements" or something else.To get something to show up in the console, you'll use the

console.logfunction like this:<script> console.log('there is some js running here'); </script>If you save that and reload you should be able to see the output in your browser's console.

Now that we are able to log things to the console, let's quickly learn some basic js elements. And it makes sense to start with variables, because we can't write very interesting (if any) code without them. Start with the following:

<script> // declare my variables var a = "web"; var b = "site"; var c = 24; var d = 7; // perform some operations and store them in new variables var firstResult = a + b; var secondResult = c + d; var thirdResult = b + d; var fourthResult = c/d; var fifthResult = c + "/" + d; // log out all the results console.log(firstResult); console.log(secondResult); console.log(thirdResult); console.log(fourthResult); console.log(fifthResult); </script>Take a moment to zip through this if you haven't done much with js yet and try to get a sense of why you're seeing the output you're seeing. Note that you get a number if you perform operations with numbers (

secondResultandfourthResult), but that as soon as you add strings--even a single string--to the mix, the output is a string. For more info on the sorts of values you can store in variables, check out the mdn reference.Also note that those lines beginning with

//don't really do anything when the code runs; they just convey information to you and other coders as you read the code itself. These are comments, and it's usually a good idea to include them to note what the various chunks of your code are accomplishing (even once you have loads of experience coding, you can still get confused by stuff you wrote 6 months ago).Logging to the console is a valuable technique while developing your site, but ultimately you'll want to use your code to do something to the elements on your page, and there's one key method you'll use again and again to "grab" elements of the page and manipulate them. Paste the following chunk of code into your script:

var bigBox = document.querySelector('#big-box') bigBox.innerHTML = "NEW TEXT HERE";What we're doing here is looking through the document (i.e. your webpage) for an element with an

idequal to#big-box, and we are storing that element in the variablebigBox. We are then changing theinnerHTMLofbigBoxto be a message of our choosing. Save this, reload your page, and you should see your new message show up in the big box.functions // simple

functions // addEventListener

conditionals // add additional buttons to div and do event delegation?

arrays

objects

loops

other libraries // YouTube or Vimeo API? (insert player, change h1 to video title, insert marker button, display marker ts)

Creating routes and views

- Take a look at lines 10 & 27 in

app.js. You'll note that they requireroutes/index.jsand declare that we'll use whatever's there when users make requests at the'/'endpoint (i.e. the root of the site we're building). To see what's currently going on in more detail, let's open up/routes/index.jsin the left pane on Atom and/views/index.ejsin the right pane. Inindex.jswe find the following:

Here we're saying that when a user makes a get request we are going to render a template calledrouter.get('/', function(req, res, next) { res.render('index', { title: 'Express' }); });'index', and we're going to pass in a javascript object full of data we want the template to render somehow. In this case we're just sending in a title for the page, but we could be sending in urls of images, user data, giant arrays of information from our database, etc. etc. To test this out, change the value oftitleto'Simple Slack App', quit the server by entering control+C in the terminal, restarting the server by enteringnpm start, and then reloading localhost:3000. - It is a pain to have to restart the server every time you change the server-side code, so we're going to run our app with a utility called

nodemonthat automatically restarts the server every time we change something. To do this:- enter

npm install -S nodemonto install it and add it to your dependencies - open up your

package.jsonfile and add a new script calleddevstartin the scripts section with the valuenodemon ./bin/www. When your done, your scripts section should look like this:"scripts": { "start": "node ./bin/www", "devstart": "nodemon ./bin/www" }, - now when you want to start the app, instead of typing

npm startwe'll typenpm run devstart. Do this and you should be able to open up localhost:3000 again. Try changing something in your index route to see if the change is working.

- enter

- Now, over in

views/index.ejsyou can see where thetitlevalue is being sent. In line 4, we find<title><%= title %></title>, in line 8 we find<h1><%= title %></h1>, and in line 9 we find<p>Welcome to <%= title %></p>. In each of these three cases, the string 'Simple Slack App' is being passed in and rendered, just as if you would have typed<title>Simple Slack App</title>into a regular HTML file. The strange<%= %>tags are what we need to use to access thetitle, and instead of having to typedata.titleor some such, as you might expect, we get to just use the properties of the object we pass in (fromindex.js) as variables (inindex.ejs). We'll also be able to add plain old js (loops, conditionals, etc.) to the.ejsfiles using<% %>instead of<%= %>, but let's not worry about that yet. To make sure you're grasping how this works, add another property/key along with another value, perhapssubtitle: 'My First App'or something like that. Then, over in theindex.ejsfile, do something with it, like maybe<h2><%= subtitle %>. - So let's now create a new route in the

index.jsfile. Copy and paste in the following code:

This listens for people to make requests to therouter.get('/slack-history', function(req, res, next){ res.send('Slack History will go here.') })/slack-historyroute, and in response the server will send back a simple text message. This may not seem useful, but believe it or not this is more or less exactly what we'll need to do later on to register our URL with our Slack App. - If you want to do something more interesting than sending simple text back, try the following:

- create a duplicate of the

index.ejsfile in/viewsthat you callslack_history.ejs(this is easier than starting from scratch) - change the block of code above by swapping out the

res.sendline for the following:router.get('/slack-history', function(req, res, next){ var message = "Ultimately, we'll put our Slack App here. The variable we're passing in here could contain anything." res.render('slack_history', {title: "Slack History", message: message}) }) - now let's make use of the extra value we're passing in. Over in

slack_history.ejs, add in a paragraph for themessageby adding the following code:<p> <%= message %> </p>

- create a duplicate of the

- To really take things to the next level, let's pass in a larger array of data and then handle that over in the ejs. Add in the following array (or a similar array) as a variable in your

router.get(/slack-history, . . . )route:

You can find a much larger and more interesting array here if you want to go above and beyond. Once you have some data stored in a variable, go ahead and pass that on to the ejs template, the object you send should now look something like this:var sampleData = [ { "city": "New York", "population": "8405837", "state": "New York" }, { "city": "Los Angeles", "population": "3884307", "state": "California" }, { "city": "Chicago", "population": "2718782", "state": "Illinois" } ]{title: "Slack History", message: message, data: sampleData} - To take advantage of all the data you send to the ejs template, you'll need to handle it over there with a loop. It will be similar in every respect to a basic js loop, but we'll need to use those

<% %>tags to set it off from the HTML. Try adding in the following if you copied and pasted the array above, or edit this code appropriately if you brought in different data.

Here we start up an ordered list, then inside the<ol> <% for(i=0; i<data.length; i++){ %> <li> The population of <%= data[i].city %> is <%= data[i].population %>. </li> <% } %> </ol><ol>tags we write a loop in js that loops through the data array. Then, insidelitags, we create a sentence for each elementdata[i], calling its.cityand.populationproperties. - include partials

- loop through links in json

Forms, Posts, MongoDB

- // create simple form

- // create route

- // test

- //

Deploying with Heroku CLI

Things are way easier if we have this app running out on the internets rather than on your machine when we head on to the next steps, so in this step we're going to learn how to deploy this app using Heroku.

Heroku already has an amazing tutorial for developers wanting to deploy node.js apps, so check that out if you have time. Here we'll try to be even briefer, and to really focus on the bare minimum you need to know for this tutorial.

- Head to Heroku and sign up for an account if you don't have one already.

- Download and install the Heroku CLI here.

- In your Terminal, enter

heroku loginand log in with your Heroku user name and password. - Now, again in the Terminal, and again making sure that you are in the root folder of your app, enter

heroku create. - To get the app to run properly, we need to let Heroku know how to start, and to do this, we create a file at the root of the app named

Procfile(no extension needed), and inside it we'll paste the following code:

And that should be it (unless you have some environment variables, like a MongoDB url, say, in which case you can check out how we solve this problem with our secret Slack credentials below).web: node ./bin/www - We are assuming that you are all set up with git, and used to the

git add .+git commit -m "message"+git push origin masterprocess you've probably repeated a bunch by now. We're now going to add an additional command to this refrain:git push heroku master, which will push the repository up to Heroku. - Now if you enter

heroku openyou should see your default browser open up your Heroku site. Make a note of the URL--or, even better, slack it out to the team to celebrate! You'll need that URL, because you'll be pointing your Slack commands at it in a bit.

Starting a Slack App

create a new slack team for yourself

maybe create a couple of different users so that you can test out privacy-related settings, etc.

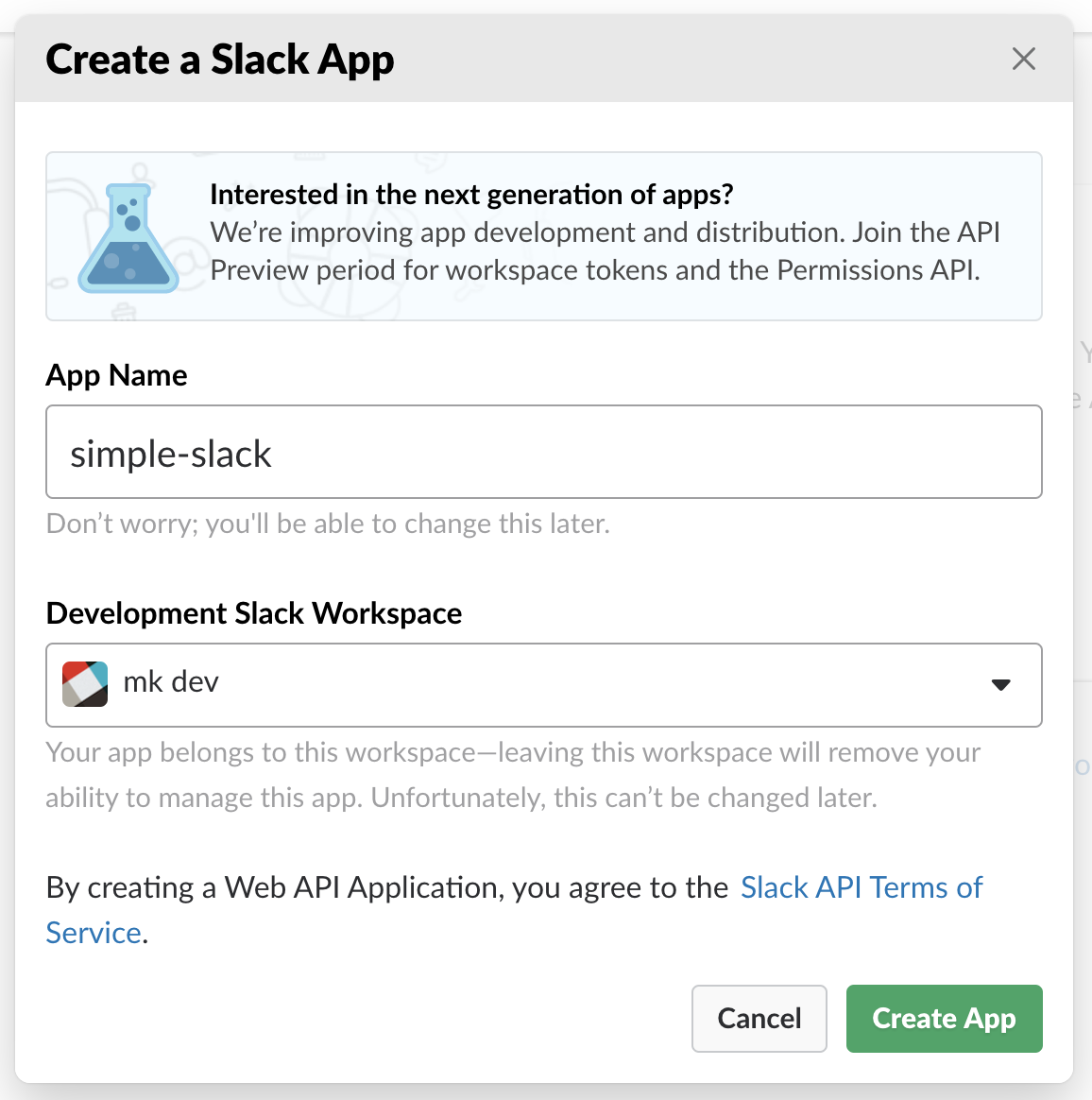

head to api.slack.com/apps, where you should be able to see a big "create Slack App" button. Click it and call your app whatever you like. We'll call ours

simple-slack. .

.next up, we're going to do a bunch of stuff in the "add features and functionality" section. Start by clicking "Incoming Webooks". Toggle the on/off switch to "on".

Towards the bottom of the page, you'll find an "Add New Webhook to Workspace" button. You'll then be prompted to approve this webhook for posting to a specific channel, and once you do this, you'll be able to copy the slack webhook URL.

To test if it's working, you can copy and paste the "Sample curl request" that gets generated for you and paste it into your Terminal. This command should send a message to your chosen Slack channel.

This webhook URL, and all the other secret keys and tokens you get from Slack, Mongo, etc, should be kept secret, and this means keeping them off of github. So don't just add these to app.js. Instead, create a file named

.envin the root folder and save your tokens and keys there. In this case, it should have the following format:SLACK_WEBHOOK=https://hooks.slack.com/services/ABCDE1234/XXXXXXXXXetc.If you click "Basic Information" at the top of the lefthand sidebar, you'll find three other secret strings you'll want to save securely. You can call them

SLACK_CLIENT_ID,SLACK_CLIENT_SECRET, andSLACK_VERIFICATION_TOKENas you add them to your.envfile.If you're wondering how to access these variables from within your app, all you have to do is

- Install

dotenvby typingnpm i -S dotenvinto the Terminal (while in your app's root folder of course) - Add the following line near the top of your

app.jsfile:require('dotenv').config(); - To check if this is working, try adding

console.log(process.env.SLACK_WEBHOOK)toapp.jsand seeing if it logs the right thing out. This is happening on the server side, so your users won't see it (which they WOULD if you were logging it in their web-browser consoles)

- Install

CHANGE NOW: You may already be wondering whether or not that

.envfile with all of its special variables has made its way up to Heroku ongit push heroku master, given that you've already told git not to include any files starting with.–– this is a good thing to worry about. He have to tell Heroku about our environment variables by typing the following:heroku config:set SLACK_WEBHOOK=After that, you shouldn't need to mess with them again unless their values change.

Now we're going to zip through a bunch of the settings we can access through the links in the "Features" section of the left sidebar.

Creating a Slash Command

- Once you click on "Slash Commands" in the left-hand sidebar, you'll see a "Create New Command" button, which you should click.

- Now you need to make some choices.

- You'll need to give your command a name, well just use

/simplefor now - for the request URL, you'll need to paste in your Heroku URL and then add on a route. We'll use

/simple-slash. Once you do this you may be prompted to reinstall your app, and you can go ahead and do this.

- You'll need to give your command a name, well just use

- Once Slack is pointed at your

/simple-slashendpoint, you need to create a route (and make sure that it's running on Heroku, not just on yourlocalhost:3000, because Slack can't seelocalhost:3000). So go ahead and add aPOSTroute to yourroutes/index.jsfile:

After this, you should be able to therouter.post('/simple-slash', function(req, res, next) { console.log("got a request:"); console.log(JSON.stringify(req.body, null, 4)); res.send('just received a message. will do more soon') })git add .,git commit -m "message",git push heroku masterdance to get things running on the Heroku server, and after that your slash command should be live. Type/simple testinto Slack and you should see some sort of result, both on the client side (in Slack), and on the server side, where you are logging out stringified JSON of thereq.body. Don't forget that you need to be checking your Heroku logs withheroku logs --tailrather than checking the terminal you typednpm run devstartin. - The next thing to do is to poke around in the req.body to get a sense of what's there. You'll note that the slash command itself is

req.body.command, the user is there as both areq.body.user_nameand areq.body.user_id, and that the text isreq.body.text. These are the key values we'll use to develop our response. For starters, why not personalize the response by trying to say something toreq.body.user_namein particular? - You can send back more than simple text, however, and to do so you'll want to construct a JSON 'payload' object that looks something like this:

And now that you've defined it, send it to slack:var thePayload = { text: "received your message", attachments: [ { title: "just a simple gif", image_url: "https://gph.is/1GrHtOZ" } ] }

If you restart the app (by committing and pushing to heroku) you should see the results when you type the slash command into Slack.res.json(thePayload); - There are many more things you can add to the messages, including color options, footers, timestamps, etc. We are going to concentrate on adding buttons, because they'll allow our users to communicate with our app. To start, interactive messages

- message permanence

Enable Interactive Components

Start by clicking "Interactive Components"

You'll need to paste in a URL for the API endpoint you are going to build in your simple-slack app. So copy your Heroku URL and paste it in, and then add a slash and a name you'll remember. Something like

https://rocky-earth-53316.herokuapp.com/slack-interactionsThat

/slack-interactionsis a route you are going to have to build. So open up theindex.jsfile in yourroutesfolder and start with the following code:router.post('/slack-interactions', function(req, res, next) { console.log(JSON.stringify(req.body, null, 4)) res.send('got your message'); });As usual, don't just paste but try to make sure you get what each part of this code is doing.

handle?

OAuth and Permissions

We aren't going to cover how to manage OAuth verifications in this tutorial (you will have master OAuth if you want to distribute your Slack App to the broader public). But we need to dive into the elements we'll find on the "OAuth and Permissions" page (accessible via sidebar link). This is where we'll specify which API methods we'll enable for our app. You might think that you may as well enable everything and then figure out what to use later on. And you could do this. But it is generally safer to limit your app's permissions to only the methods you really really need.

- The first thing we'll do on this page is copy the OAuth Access Token, and we'll save this to our

.envfile as as theSLACK_TOKEN. - Next, we'll scroll down to the "Scopes" section, and we'll select a number of scopes to add:

channels.historychannels.readchannels.writereactions.readusers.readAdd these one by one, click save, and then click to reinstall the app (when it asks you again for a specific channel, this is just for the webhook you installed--go ahead and choose the channel you want webhook messages to go to again--you will still be able to send messages to other channels using the Web API).

- If you are in a hurry to see what the methods that use these scopes can do for you, go ahead and create a legacy token and test out the channels.list method (or any others that match scopes you've added). You can generate the exact same JSON we'll later generate in our app through the Slack API website. And you can even get a URL that will send back your raw JSON (though Slack suggests that you move away from using these tokens in favor of the OAuth tokens). In this tutorial we are going to hold off on using these methods, but we'll get to them soon.

Event Subscriptions

- enable them

- URL:

https://rocky-earth-53316.herokuapp.com/slack-events - select a bunch

Add a Bot user

- Click Bot users

- Add Bot User (simpleslack)

Using the Web api

1.

The Slack Node package

Much of our work will be greatly simplified by the @slack/client node package. Let's install that and get it working.

the Slack package can be found on npm and installed with the shell command

npm i -S @slack/client.for now, let's require it in our

routes/index.jsfile and test it out there. Type the following near the top of your code (which is borrowed entirely from Slack's guide to the node SDK, if you want even more info on all this):const { WebClient } = require('@slack/client'); const token = process.env.SLACK_TOKEN; const web = new WebClient(token);Now, you need to make sure that you called your token (found on the OAuth page)

SLACK_TOKENin your.envfile, otherwise this isn't going to work. (And if you want to know why there are{}aroundWebClient, you'll have to learn a bit about js destructuring).To start out, we're going to create a page that simply lists all of our Slack channels, giving the user the opportunity to select one and ask for the last 20 messages posted there. We will create a new route called

slack-channelsfor this, and we'll use the WebClient we stored inwebto ask Slack for the list of channels:router.get('/slack-channels', function(req, res, next){ web.channels.list() .then((data) => { console.log(JSON.stringify(data, null, 4)); res.render('slack_channels', {title: "Slack Channel List", message: "here are your slack channels", data: data.channels}) }) .catch(console.error); })Once you add this, you'll be sending your channel list to the

slack_history.ejsview, but you'll need to make sure that whatever you're doing in that file matches the structure of the js objects you are passing in. Here is a sample of what the objects you get from Slack will look like:{ "id": "X9JKAG8J3", "name": "test-channel-001", "is_channel": true, "created": 1520624742, "is_archived": false, "is_general": false, "unlinked": 0, "creator": "U3PL364JK", "name_normalized": "test-channel-001", "is_shared": false, "is_org_shared": false, "is_member": true, "is_private": false, "is_mpim": false, "members": [ "U3PL364JK", "U4PL364JL" ], "topic": { "value": "", "creator": "", "last_set": 0 }, "purpose": { "value": "just a test", "creator": "U3PL364JK", "last_set": 1520624742 }, "previous_names": [], "num_members": 2 }And to handle this in the

slack_history.ejsfile, you might do something like this:<body> <h1><%= title %></h1> <p>Welcome to <%= title %></p> <p> <%= message %> </p> <form action="/slack-history-post" method="post"> <% for(i=0; i<data.length; i++){ %> <input type="radio" name="channel" value=<%= data[i].id %> <label> <%= data[i].name %> </label><br /> <% } %> <div> <button type="submit">Submit</button> </div> </form> </body>In this form, we'll set the

valueto the channel's.idproperty, because that's actually what we'll be using when we communicate with Slack.

EXTRAS

- Working from elsewhere. If you begin working on another machine, you'll need to clone your repository there,

npm installall the packages, and you'll have to create a.envfile for all the secret info again. You will also need to reconnect to heroku too:heroku git:remote -a thawing-inlet-61413